GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

Manmade climate change is now dwarfing the influence of natural trends on the climate, scientists say.

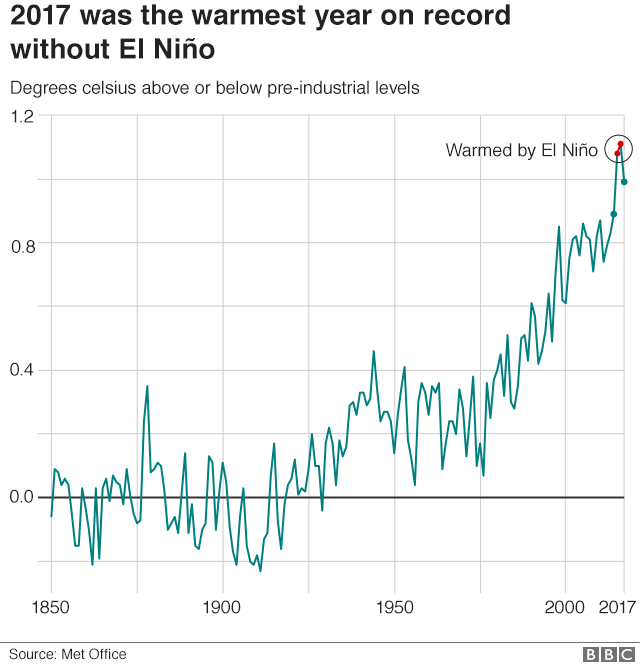

Last year was the second or third hottest year on record - after 2016 and on a par with 2015, the data shows.

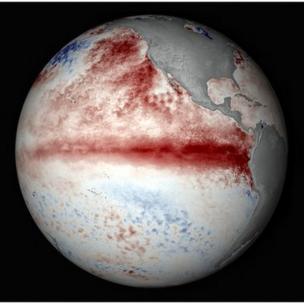

But those two years were affected by El Niño - the natural phenomenon centred on the tropical Pacific Ocean which works to boost temperatures worldwide.

Take out this natural variability and 2017 would probably have been the warmest year yet, the researchers say.

The acting director of the UK Met Office, Prof Peter Stott, told BBC News: "It's extraordinary that temperatures in 2017 have been so high when there's no El Niño. In fact, we’ve been going into cooler La Niña conditions.

"Last year was substantially warmer than 1998 which had a very big El Niño.

"It shows clearly that the biggest natural influence on the climate is being dwarfed by human activities – predominantly CO₂ emissions."

NOAA

NOAA

Figures were published on Thursday by the world’s three main agencies monitoring global temperatures: the UK Met Office and the two US organisations - the US space agency (Nasa) and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Noaa).

Their datasets are compiled from many thousands of temperature measurements taken across the globe, from all continents and all oceans.

Temperatures for 2017 and 2015 are virtually identical.

Nasa rates 2017 the second hottest year, and Noaa and the Met Office judge it to be the third hottest since records began in 1850.

The Met Office HadCRUT4 global temperature series shows that 2017 was 0.99C (±0.1C) above "pre-industrial" levels – that’s taken as the average over the period 1850-1900.

It was 0.38 (±0.1C) above the 1981-2010 average.

The Exeter-based agency calculates that the El Niño event spanning 2015-2016 contributed around 0.2C to the annual average for 2016. But that influence was gone by 2017.

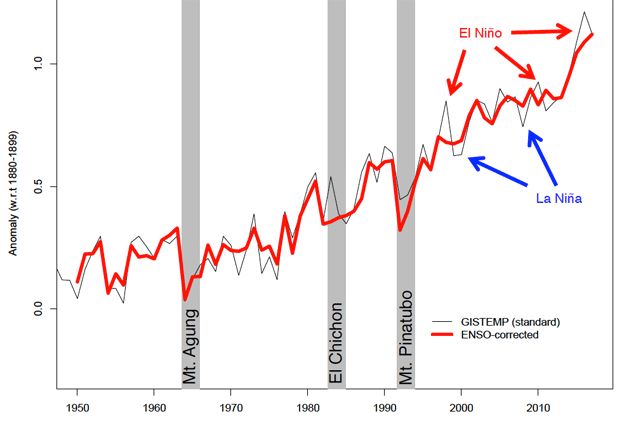

Nasa has done an additional statistical analysis that corrects its dataset for the effects of El Niño/La Niña - to smooth out the "lumps and bumps" these patterns introduce into the long-term trend.

When this is done, 2017 becomes the warmest year on record.

Nasa's Dr Gavin Schmidt said this "idealised scenario" underscored the central message: "The warmth that we're seeing, and the trends that we're seeing, are independent of this variation in the Pacific and while the ins and outs of any particular year are affected by it - it's the long-term trend that's really pushing these numbers up."

'Smoothing out El Niño/La Niña effects'

NASA

NASA

Nasa says it is possible statistically to remove the natural warming and cooling effects that come from El Niño and La Niña. When this smoothing is done (red line), 2017 comes out warmer than any previous year. The grey columns denote major volcanic eruptions that ordinarily depress the warming trend.

The World Meteorological Organization Secretary-General Petteri Taalas said the long-term temperature trend was far more important than the ranking of individual years.

"That trend is an upward one," he said. “Seventeen of the 18 warmest years on record have all been during this century, and the degree of warming during the past three years has been exceptional.

“Arctic warmth has been especially pronounced and this will have profound and long-lasting repercussions on sea levels, and on weather patterns in other parts of the world.”

Prof Tim Osborn from the University of East Anglia said climate models were now accurately predicting which places would warm fastest. He explained: “We’re seeing greater warming over land and in the Arctic regions, and less warming in the sub-polar oceans.

“These are what we expect from our understanding of climate physics, and this is what we observe.”

He said uncertainties arising from incomplete global coverage of weather stations had been included in the calculations.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

Commenting on the figures, Bob Ward, from the Grantham Institute at the London School of Economics, pointed out that this year governments were due to start assessing the gap between their collective ambitions for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and the goals of the Paris climate agreement, to stabilise temperature rise below 2C, and as close to 1.5 as possible.

“The record temperature should focus the minds of world leaders, including President Trump, on the scale and urgency of the risks that people, rich and poor, face around the world from climate change," he said.

Earlier this week, a study in the journal Nature concluded that climate change needed urgently to be tackled, but forecast that apocalyptic predictions of a temperature rise of 6C by 2100 would not come about.

Prof Richard Allan from the University of Reading said: “Rather than warming being inconsequential or catastrophic, as some have suggested, we can be sure societies are facing a dangerous temperature rise, but one which we still have time to fix.

“The conclusions confirm that human-caused climate change is a serious concern.

“But if we act now with sustained and substantial cuts in greenhouse gas emissions, societies will still be able to avoid much of the most dangerous climate change predicted by computer simulations.”

Other temperature analyses exist apart from the "big three", but these all tell broadly the same narrative. The European Centre for Medium Range Weather Forecasting issued its bulletin on 4 January. It called 2017 as the second warmest on record.